Incredible photos capture life on World Heritage sites before they were listed

Prior to the first fossil discoveries in the 1970s, the Naracoorte Caves were an extended playground for the locals.

Today they are revered as truly special places in Australia — recognised by World Heritage as sites to be protected and preserved — but there was a time when they were just playgrounds for the local kids.

So what has changed for those magnificent places and the people who lived next to them now they’ve been recognised by UNESCO and placed on its most important list of sites from around the world?

Erika Vickery was one of the children who, 40 years ago, couldn’t have known that the bones she and other students were playing with on their school excursion in South Australia were actually 500,000-year-old fossils.

Ms Vickery was on an excursion with Naracoorte High School’s Naturalist History Club.

The objective, to map a set of caves, was an easy task for the teenagers, who had spent their lives exploring an area that would soon be world-famous for filling in the blanks of Australia’s mammal history.

“The neighbourhood children all got together and we’d ride out there for the day, take a packed lunch and off we’d go,” Ms Vickery said.

“We explored the caves all on our own … it was a wonderful extended playground.”

Ms Vickery has since become the mayor of Naracoorte and is responsible for health and safety in her district, including the caves, which in 1994 were listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

“We were probably some of the first young people to actually see the fossil residues there,” Ms Vickery said.

“I’m not sure if we absolutely understood the significance of what we’d seen.”

‘A beautiful part of life’

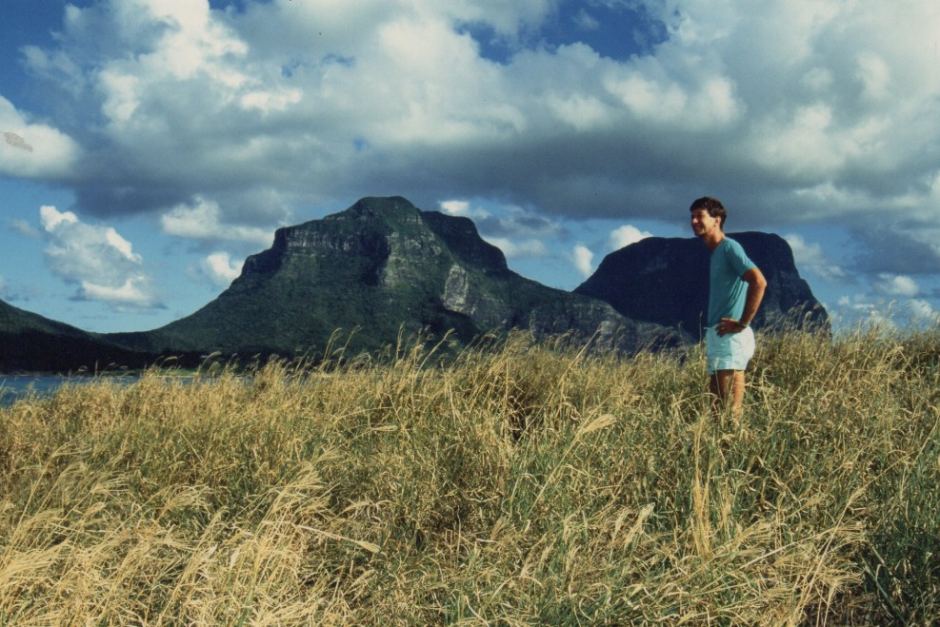

Further north, in the clear waters of the Tasman Sea, Chris Murray recalls days of snorkelling, swimming and barbecuing on Lord Howe Island without a care in the world.

“You were in the environment all the time,” Mr Murray said.

“I lived a continuum of where I didn’t have to split life up into these blocks of work and play.

“It was a beautiful part of life.”

One of the 400 people who get to call Lord Howe Island home, Mr Murray moved to the island as a child in 1958 and never really left.

Twenty years into what would be his six decades on the island, Mr Murray realised his idyllic existence needed rethinking, and when a small conservation group formed in the late 1970s, he joined.

“I started to become concerned about some of the pressures that were developing on the island,” he said.

“Some of the problems … weren’t being dealt with just because the community wasn’t well enough resourced.”

Over the years the group discussed how to counter future development on the island, how to deal with feral animals, and how to secure funding for scientific research.

In 1992 Lord Howe was awarded World Heritage status, leading to two thirds of the island becoming a permanent park preserve, free from future development.

Visitation was limited to 400 people on the island at one time, and domestic cats were banned.

In 1999 a marine park was proclaimed and fishing was banned in 30 per cent of the island’s water.

Preserved for future generations

Both Erika Vickery and Chris Murray can recall people who were disappointed when these restrictions initially came into place, but time and results have washed those feelings away.

For Ms Vickery, it took time to realise the loss of their ‘extended playground’ would mean unforeseen benefits long after their time there.

“I can see now that … it needed to be preserved for future generations and what they’ve done now is really terrific,” she said.

Mr Murray is also thankful for the preservation, which removed “that existential anxiety that I had.”

“There’s a sense that I can enjoy it without thinking, ‘well, this is the last time I’ll see [the island] like this.’

“It’s more beautiful than it was back then.

“Sea birds that were only nesting on the offshore islands have now returned in larger numbers to the main island.”

Budj Bim’s owners commit to country

For Denis Rose, a Gunditjmara traditional elder from Western Victoria, the World Heritage listing of Budj Bim this year restored more than nature — it is preserving a culture.

In 1984 the original owners had control over just two acres of the land, at the cemetery, but after decades of court cases and lobbying, ownership of 3,000 hectares of land has been returned to the traditional owners.

“We were dispossessed from our land and from our traditional practices, by and large,” Mr Rose said.

“We want our mob to get back out on country and actually enjoy country… we need to be able to enjoy what we’ve got back and get a better understanding of what’s there.”

Mr Rose expects three things to come of the World Heritage status — recognition of what the Gunditjmara ancestors did there, better protection and management of the land, and increased tourism.

It is an exciting opportunity for the traditional owners to protect and restore an example of one of the world’s oldest agricultural systems.

“We’ve got a lot of work in front of us,” Mr Rose said.

“We’ll try our very best.”