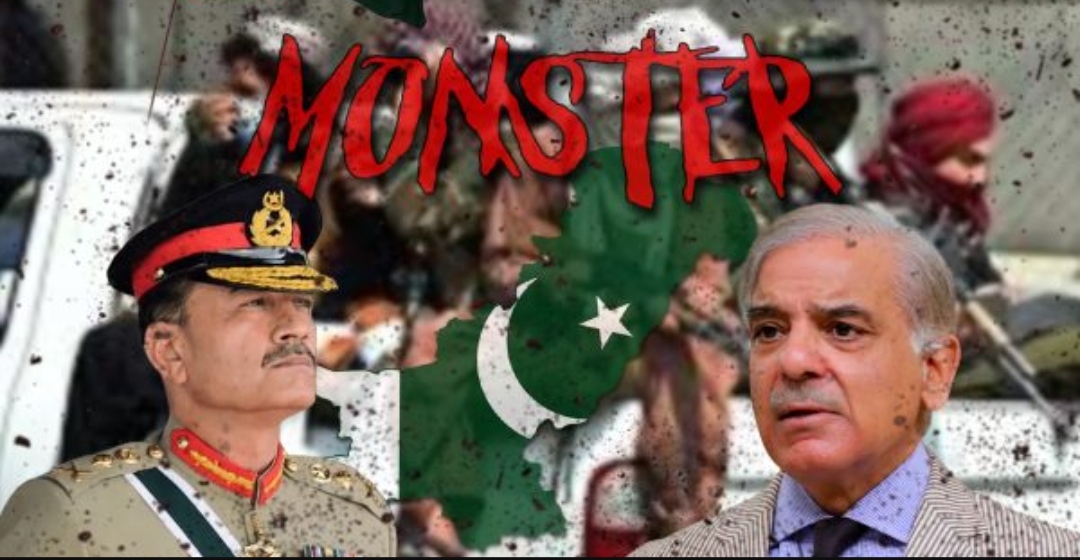

The Pakistan created monster is now devouring it and Afghanistan

By Arun Anand

There is a dark irony unfolding in South Asia: Pakistan, long accused of nurturing militant groups as tools of regional influence, is now locked in open conflict with Afghanistan over the very monsters it helped create. The war Islamabad now wages on Afghan soil, under the pretext of destroying the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), is in many ways a war against its own reflection.

For decades, Pakistan cultivated militant networks for strategic depth, funded radical religious infrastructure, and tolerated extremist ideologies under its nose. Now, those networks have turned inward, destabilizing its own borders and forcing it into the position of aggressor, violating Afghanistan’s territorial integrity and further endangering a region already trembling under the weight of instability.

The roots of this crisis reach back to the 1980s, when Pakistan became the staging ground for the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan. With U.S. and Saudi funding, the Pakistani military and its intelligence arm, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), trained tens of thousands of fighters, funneled weapons through the tribal areas, and radicalized a generation in the name of religion and nationalism.

This vast militant infrastructure did not disappear after the Soviet withdrawal—it metastasized. By the 1990s, Pakistan supported the rise of the Afghan Taliban, viewing them as a proxy to ensure a friendly regime in Kabul and to deny India any foothold. That same policy of weaponizing extremism spilled back into Pakistan’s own territory, where groups that once served Islamabad’s ambitions turned rogue, seeking to impose their own version of Islam by force.

The TTP emerged in 2007 as a coalition of various Pakistani militant factions. Its founding leader, Baitullah Mehsud, was a product of the tribal belt in Waziristan, trained in the same jihadist ecosystem Pakistan had helped sustain for decades. Initially tolerated as a buffer against local insurgencies, the TTP began to challenge the Pakistani state directly, attacking military convoys, police installations, and schools.

From 2007 to 2024, TTP attacks have killed more than 85,000 Pakistanis, including civilians and soldiers, according to Pakistan’s own counterterrorism statistics. Yet the irony is inescapable: the group’s ideology, recruitment networks, and funding channels are all descendants of the very militant infrastructure that Pakistan’s military establishment built, nurtured, and exploited.

In recent years, Islamabad has sought to portray itself as the victim of cross-border terrorism, arguing that the TTP now operates from sanctuaries in Afghanistan. There is truth in the claim that many TTP fighters fled across the Durand Line after Pakistan’s military offensives in 2014 and 2017. But the more fundamental truth is that these sanctuaries exist only because Pakistan drove them there after years of manipulation and failed peace deals.

Now, when the TTP stages attacks on Pakistani soil, Islamabad responds with airstrikes and artillery fire across the border, violating Afghan sovereignty and causing civilian casualties. In March 2025 alone, more than 40 civilians were reported killed in air raids in Khost and Paktika provinces. In September, Pakistani strikes near Nangarhar and Kunar killed at least 60 people, including women and children, according to Afghan local authorities.

The toll is rising monthly, and the conflict risks spiraling into a wider confrontation between two nuclear-armed neighbors. The cost to human life is staggering. Since August 2021, when the Taliban regained power in Kabul, more than 1,200 people have died in Pakistan-Afghanistan border clashes, including 380 civilians.

Over 600,000 Afghans have been displaced from eastern provinces due to Pakistani bombardment, while thousands of Pakistani civilians living in frontier districts have fled their homes because of TTP incursions. Trade routes between Torkham and Spin Boldak have been repeatedly closed, crippling the livelihoods of thousands of traders. The border, once porous but functional, has turned into a militarized zone of suspicion and fear. Afghan officials accuse Pakistan of acting like an occupying power, while Islamabad justifies its actions as “preventive counterterrorism.”

But there is nothing preventive about indiscriminate bombing. Every missile that lands on Afghan soil deepens the resentment of ordinary Afghans and fuels the anti-Pakistan sentiment that militants thrive upon. At the core of this escalation is Pakistan’s refusal to confront its own culpability. The TTP was not born in a vacuum; it was engineered by decades of policy that saw militant groups as assets. Pakistan’s military establishment has long differentiated between the “good Taliban,” who operate in Afghanistan and serve Islamabad’s regional interests, and the “bad Taliban,” who attack within Pakistan. This cynical dichotomy has collapsed.

Fighters once trained for operations in Afghanistan have turned their guns inward, angry at Pakistan’s cooperation with the United States and its repression of Islamist networks. The same madrassas that produced Taliban ideologues in the 1990s continue to churn out young men steeped in extremist ideology. The result is a conveyor belt of radicalization that Pakistan itself struggles to turn off.

Economically, the blowback has been disastrous. The war on terror, combined with Pakistan’s internal insurgency, has cost the country over $150 billion in lost GDP since 2001. Foreign investment has fled. Security spending consumes nearly 20% of Pakistan’s federal budget, leaving little for education, health, or infrastructure. Inflation has soared, unemployment is at record levels, and public trust in the military—the country’s most powerful institution—is crumbling.

For ordinary Pakistanis, the state’s obsession with controlling Afghanistan through militant proxies has produced nothing but perpetual insecurity and poverty. The narrative that Pakistan is itself a victim of terrorism rings hollow when one remembers that it was Pakistan’s own state machinery that created, sheltered, and armed the very groups now tearing it apart.

Afghanistan, meanwhile, suffers the consequences of Pakistan’s militarism. Its fragile economy, already devastated by sanctions and international isolation, is further strangled by border closures and bombings. Afghan villages in Khost, Paktia, and Kandahar have been hit multiple times by Pakistani airstrikes that claim to target TTP hideouts but often strike homes and mosques. The death toll in Afghanistan since Pakistan began its cross-border operations in 2022 has surpassed 2,000, including hundreds of women and children. Each attack drives a deeper wedge between the two nations and pushes Afghanistan closer to resentment, revenge, and radicalization. In the absence of legitimate international mediation, these tit-for-tat escalations could ignite a full-blown war, one that would destabilize the entire region. The implications for South Asia’s peace are dire.

With India and Pakistan already locked in a frozen hostility, any further militarization of the Pakistan-Afghanistan border threatens to open another front in the regional security crisis. The influx of refugees, cross-border militant flows, and smuggling networks will exacerbate tensions across Central Asia. China, which has invested billions in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, faces growing insecurity in its western projects. Iran, too, fears the spillover of militancy into its eastern provinces. South Asia’s peace, already hanging by a thread, could unravel completely if Pakistan continues to externalize the consequences of its own policies.

The argument that Pakistan is the epicenter of global militancy is not mere rhetoric—it is borne out by data. Of the world’s twenty most active terrorist groups identified by international monitoring agencies in 2024, at least six originated or operate primarily from Pakistani soil. Pakistan remains the only country where three distinct Taliban movements—Afghan Taliban, Pakistani Taliban, and various splinters—coexist, often with overlapping logistics and ideological networks. From Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed to the Haqqani Network and TTP, these groups share the same genealogical tree: nurtured by Pakistan’s security apparatus under the illusion of strategic control. The result is a self-perpetuating cycle of violence that has not only consumed Pakistan but also undermined peace from Kabul to Kashmir but India has now called its bluff.

Pakistan’s strategy of plausible deniability—funding, training, or tolerating militants and then denying responsibility—has reached its end. Now even the international community increasingly sees Pakistan not as a victim of terrorism but as a hub of it. Its actions in Afghanistan—airstrikes, cross-border raids, violations of sovereignty—expose its desperation to contain a monster that no longer obeys. The TTP’s resurgence is the final proof that Pakistan’s policy of using terrorism as an instrument of statecraft has imploded. The creator has lost control of its creation.

The tragedy is that ordinary Pakistanis and Afghans pay the price. In both countries, generations have known nothing but war, displacement, and loss. The children of the madrassas and refugee camps, born into poverty and indoctrination, become the cannon fodder for wars they never chose. Every time a bomb falls, another cycle of vengeance begins. The only way to end this is for Pakistan to dismantle the infrastructure of extremism it has built—its militant networks, ideological nurseries, and covert funding chains—and to accept that peace cannot be achieved through manipulation or force.

The conflict between Pakistan and Afghanistan is thus not just a border dispute or a counterterrorism campaign. It is the culmination of decades of duplicity—a nation at war with the ghosts it raised. Pakistan created the monastery of militancy, nourished it with ideology and money, and now finds itself devoured by its own creation. The flames burning along the Durand Line are not just consuming Afghan villages—they are consuming Pakistan’s own moral legitimacy, its economy, and its future. Until Pakistan confronts this truth, peace in South Asia will remain a mirage, forever out of reach, flickering behind the smoke of wars that never end.

Blitz