When a house is not a home

By Dr. Akalanka Thilakarathna

Togetherness matters in the age of nuclear families

In the 21st Century, the structure of the family, one of the most enduring social institutions, has undergone a quiet but profound transformation. Across cities, suburbs, and even rural communities, extended families that once lived, worked, and raised children together have gradually given way to smaller, more isolated nuclear units. This shift is often celebrated as a symbol of modernity, independence, and financial practicality. Yet, beneath the surface lies a deeper question: What makes a house a home?

Is it merely a building where parents and children reside? Or is it the sense of belonging, security, and collective care that flourishes when family networks remain intact? As more societies including those in South Asia move towards nuclear living, it becomes increasingly clear that physical shelter alone cannot substitute for emotional togetherness. A house may offer comfort and privacy, but, it does not automatically transform into a home without shared relationships, mutual support, and a sense of community.

The move to nuclear families, once viewed as a sign of progress, has brought subtle but significant psychological, social, and developmental challenges. Togetherness matters, particularly for the healthy upbringing of children, and societies may need to rethink what home truly means in an era of shrinking family bonds.

Fragmented families, childhoods

For generations, families were not defined merely by parents and children but by a vibrant network of grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and close family friends. This extended family model provided children with a diverse emotional ecosystem. A child who was scolded by a parent found comfort in a grandparent. A teenager struggling with peer pressure could confide in an aunt or an older cousin. Celebrations, grief, conflict, and care were shared responsibilities, creating a rich web of human connection that shaped a holistic childhood.

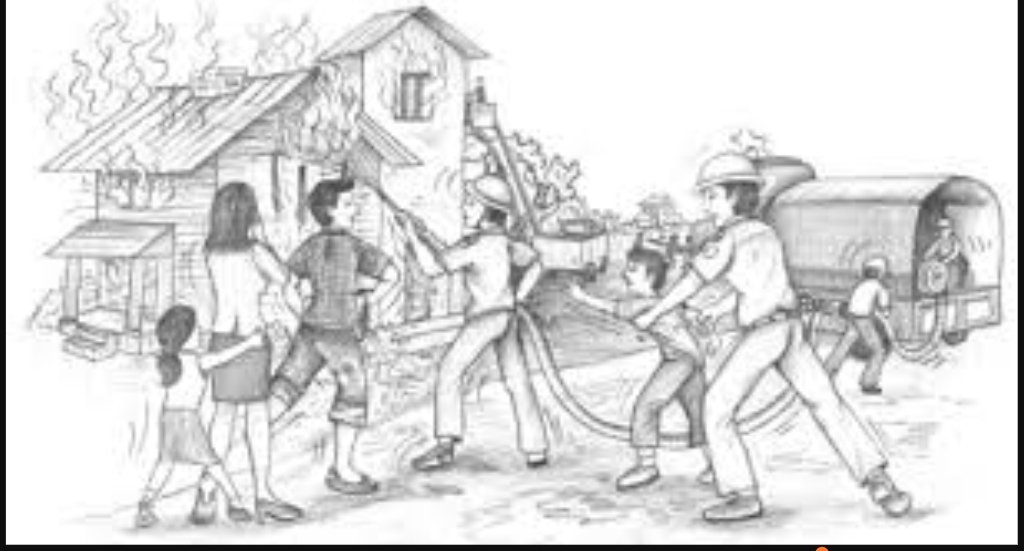

However, economic pressures, career mobility, and urban living have disrupted this structure. Young parents often move to cities in search of employment, leaving behind their elders and, with them, the everyday support system that traditionally made parenting a communal act. Although modern homes are more spacious and materially comfortable, the emotional space within them has become smaller. Children who once grew up surrounded by multiple caregivers now depend almost entirely on their parents for emotional support, guidance, and companionship.

This shrinking of the family ecosystem has a direct impact on childhood experiences. A nuclear home, however well-intentioned, often lacks the collective warmth that naturally flowed in extended households. Parents who juggle demanding jobs return home exhausted, with little time or energy to engage in meaningful conversations. Children, in turn, experience growing loneliness, spending longer hours with screens instead of people. The loss of spontaneous interactions, playtime with cousins, stories from grandparents, and shared tasks with relatives, creates a fragmented childhood experience that shapes children’s emotional resilience in the long run.

The emotional costs of going nuclear

The emotional consequences of nuclear living manifest in ways that families often do not anticipate. Research across multiple societies now shows that children who grow up in isolated family settings are more likely to experience feelings of stress, anxiety, and behavioural challenges. Parents often find themselves wondering why their children seem restless, irritable, or withdrawn, without realising the absence of a wider circle of affection and discipline plays a role.

Grandparents bring a unique kind of emotional stability to a household. Their slower pace of life, patient attention, and unconditional affection provide children with a sense of comfort that parents, busy with modern schedules, cannot always replicate. When families move towards nuclear living, this calming presence disappears. Children lose not only additional caregivers but also soft mentors who teach values through lived experience, stories, rituals, and everyday conversations.

Similarly, the absence of aunts, uncles, and older cousins removes important alternative perspectives from a child’s life. A child who struggles to communicate with a parent may find it easier to open up to a relative who understands their temperament. These relatives often act as emotional buffers, helping children navigate adolescence with greater stability.

The pressures on parents also intensify in nuclear families. With no relatives to share responsibilities, parents become the sole providers of emotional care, discipline, academic support, and moral instruction. This unrealistic burden frequently leads to burnout. The emotional climate within the home becomes tense, and children, keen observers of adult behaviour, internalise this stress. Over time, the house becomes a functional space rather than an emotionally nourishing environment.

Cultural disconnect and loss of identity

A home is not only a place for eating and sleeping; it is a living archive of culture, memory, and identity. In extended families, conversations over meals, celebrations of festivals, and collective rituals organically transmit values and traditions from one generation to another. Elders play a vital role in preserving language, storytelling, religious practices, and moral frameworks that children do not learn in school.

When nuclear families live in isolation, children often lose this connection to their cultural roots. Busy parents may prioritise work over tradition, and cultural transmissions that once occurred naturally now require a conscious effort. A child who rarely meets their grandparents may grow up with little knowledge of their ancestral stories, customs, or family history. Without this grounding, children may feel culturally adrift, especially when faced with identity-related challenges in adolescence or adulthood.

Furthermore, the weakening of cultural bonds creates a sense of emotional detachment from the larger family lineage. Children may develop a more individualistic worldview, shaped by digital influences rather than generational wisdom. While independence is valuable, identity without roots can create feelings of emptiness or confusion later in life. Extended family structures once ensured that children felt part of something larger than themselves, a sense of belonging that modern nuclear living often struggles to recreate.

Why togetherness still matters?

Togetherness, even when not physically bound to a single household, remains an essential ingredient of healthy family life. The emotional resilience of children is strengthened when they feel supported by a broad circle of relatives who love and guide them. A home infused with multiple relationships becomes a training ground for social skills, empathy, cooperation, and conflict resolution.

Living with or regularly interacting with extended family teaches children to share space, respect differences, and manage disagreements. They learn that life is not solely centred on their preferences but requires compromise and understanding. The presence of multiple role models helps children identify traits that they admire and emulate. They gain emotional security from knowing that love does not come from only one or two people but from an entire village.

Togetherness also reduces the pressure on parents. When grandparents or relatives participate in childcare, parents experience less burnout and can provide more patient and positive attention to their children. The emotional weight is distributed across generations, creating a calmer and more stable home environment. A house filled with supportive relationships becomes a place where children flourish, not merely survive.

Finding balance in a changing world

While it is unrealistic to expect all families to return to joint living arrangements, the need for emotional connection and extended support remains unchanged. The challenge, therefore, is to find creative and practical ways to preserve togetherness in an age of nuclear households.

Technology can help bridge geographical gaps. Regular video calls, online family gatherings, and shared photo albums can keep relationships alive, even from a distance. Yet, digital interaction alone is not enough. Planning frequent visits, celebrating festivals with extended family, organising family trips, or encouraging children to spend school holidays with grandparents can help rebuild emotional ties.

Parents must also cultivate community bonds. Close friendships with neighbours, school parents, and colleagues can become the “chosen family”, providing additional support networks. Encouraging children to participate in community groups, clubs, and religious or cultural activities widens their social exposure and compensates for the absence of relatives.

The broader society including schools, workplaces, and Government agencies must recognise that nuclear families face unique pressures. Policies that support parental leave, flexible working hours, and community childcare can ease the burden on parents. Schools can create programmes that involve grandparents or older community members to share stories, traditions, and experiences, helping bridge the generational gap.

Ultimately, togetherness requires intention. Families must consciously rebuild the networks that modern life has quietly eroded.

Conclusion: turning houses back into homes

A house becomes a home only when it nurtures relationships, emotional well-being, and a sense of belonging. As societies continue their march towards nuclear living, the challenge is to preserve the depth and warmth of extended family bonds. Children deserve a world filled not just with material comfort but with emotional richness, guidance, and shared memory.

If families can rebuild togetherness, even in new and adaptive forms, then, even the smallest apartment can once again become a home. In the end, it is not the size of the household but the strength of the connections within it that determines the emotional health of a child. And, it is this sense of community, continuity, and care that ensures that the next generation grows up grounded, confident, and capable of turning their own houses into homes filled with love.