How ‘Sri Lankan English’ adapted, borrowed and blended into the Oxford English Dictionary?

By Kamanthi Wickramasinghe

Be it asweddumized fields or mallung in a rice and curry meal, kiribath for a special occasion, sizzling kottu, scrumptious watalappam or a happening baila song – each one of these examples provides a glimpse of Sri Lanka in a nutshell. The aforementioned words have been used in our vocabulary for decades, highlighting the unique cultural, social and culinary diversity of Sri Lanka.

This is why these words and a few others made their mark in the Oxford English Dictionary’s (OED) latest update, in appreciation of the origins and evolution of Sri Lankan English. To find out more about how these words made their entry into a world-acclaimed dictionary, the Daily Mirror spoke to Rochana Jayasinghe, the consultant for Sri Lankan English for the OED’s World Englishes update.

A journey shaped by a fascination for language

Jayasinghe’s journey into language study had begun with a deep love of reading from a young age. “I was always fascinated by words—their histories, meanings, and the patterns that connected languages across cultures. As a child, I enjoyed learning new languages and instinctively noticed similarities among them, which I later came to understand as an early curiosity in etymology and historical linguistics,” she said.

Her academic path was shaped significantly during her time at the Department of English at the University of Peradeniya, “where conversations around language use, and in particular, World Englishes, were particularly vibrant and intellectually stimulating,” as described in her own words.

Jayasinghe said that the Department has long been at the forefront of interrogating language, identity, and post-colonialist. “Their scholarship has contributed much to thinking critically about the politics of English, the localisation of the language, and its ideological implications,” she added.

Though her formal training is in literature with a Master’s in World Literatures in English – it was through literary study that her interest in language itself deepened. “During my Master’s at the University of Oxford, I researched Sri Lankan-origin words in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), published by Oxford University Press.

My focus was on the correspondence between Robert Burchfield, then-editor of the OED, and Pearl Cooray, who was affiliated with the Dictionary Department of the University of Ceylon, later absorbed by the Ministry of Cultural Affairs. Their exchange, spanning from 1971 to 1981, offered a window into the collaborative history of lexicography between Sri Lanka and the OED.

This research led to my selection – through a vetting process, lexicographical aptitude test, and working visit – as the consultant for Sri Lankan English for the OED’s World Englishes update,” she explained.

Understanding the context of a dictionary

Apart from simplifying complex words for users, Jayasinghe opined that different dictionaries have different aims and philosophies. “So when we ask, ‘what is a dictionary, the answer depends on which one we’re talking about. I can only speak with confidence about the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), which is the one I’ve studied in depth and worked with,” she said in response to a query on what exactly is a dictionary.

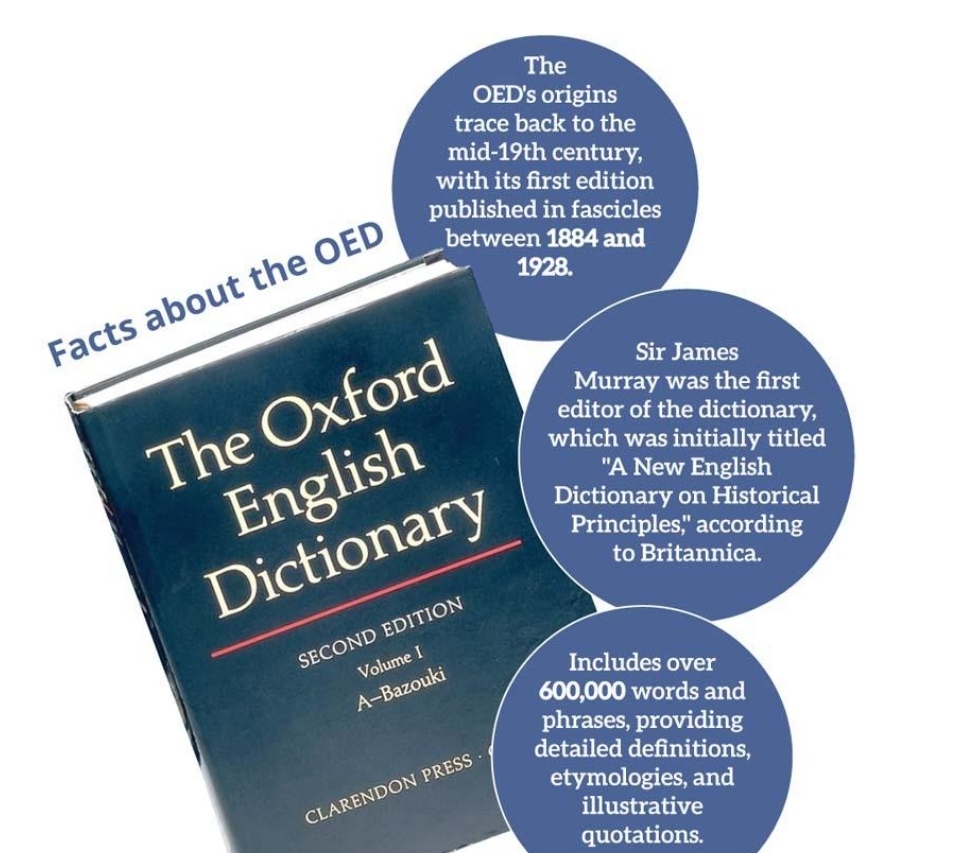

“To begin with, it’s worth noting that Oxford University Press publishes two major dictionaries: the Oxford Dictionary of English, which is a current-use dictionary aimed at offering concise definitions for everyday reference; and the Oxford English Dictionary, or OED, which is quite different.

The OED is a historical dictionary – its job isn’t only to define a word as we use it today, but to trace its full life story: where it came from, how its meaning has shifted over time, and how it’s been used in context, across literature, newspapers, legal documents, and more,” she explained.

“So, when people ask, ‘Why is a word in the OED’, it’s important to understand that the OED isn’t giving us permission to use these words—and never claimed to. That’s not its function. The OED’s role is to record how people are already using language, not to decide what is or isn’t “correct.” Sri Lankan English didn’t suddenly become “real” the moment it appeared in the dictionary. It’s been real for decades. We’ve spoken it, sung baila in it, written school essays in it, argued in it, and cracked jokes in it,” she added.

Lankan English isn’t in how different it is from British or American English, but in how it may reflect our local realities while still participating in a global language,” Jayasinghe explained.

From Asweddumize to Papare

When asked how certain words such as asweddumize made its entry into OED, Jayasinghe said that interestingly, asweddumize was one of the words everyone thought was already in the dictionary. “It has certainly been part of OED discourse for nearly a century, but it missed inclusion at the time due to insufficient evidence.

It resurfaced in 1971 with the intervention of Pearl Cooray, and again in the 1980s, but was set aside once more. Now, with broader access to historical and contemporary Sri Lankan sources, the editors were finally able to gather enough evidence – including a first recorded use from as early as 1857 – to support its inclusion,” she explained.

Jayasinghe further said that words like kottu roti, watalappam, mallung and kiribath were included because food is generally a visible and shared part of any culture, and that makes food-related terms especially likely to appear in English usage across communities. “These words frequently turn up in writing – menus, travel writing,

cookbooks, media – and are often left untranslated because there aren’t equivalent “English” words that can be used. Other terms like baila and papare were added for similar reasons,” she added.

She further said that a ‘few words didn’t make the cut this time’, but that it doesn’t mean it won’t be added in future. “The OED is a living dictionary, so words are always being revisited as new material becomes available,” she explained further.

Bringing about social harmony through sociolinguistics

The new set of words added to the OED represent diverse cultures. Speaking about the role of sociolinguistics in bringing about social harmony Jayasinghe explained that sociolinguistics shows us how people relate to each other through language. “In a multi-ethnic, multi-diverse country like Sri Lanka, where identities, histories, and cultures intertwine, language is a living expression of who we are,” she added.

But she said that with regard to the new set of words, some media outlets and social media pages have run with the headline “Sinhala words added to the dictionary!”, which is both inaccurate and unhelpful. “Many of the words we’re talking about are nourished by a rich mix of Sinhala, Tamil, Malay, Portuguese, English, and other influences, showing us that language is not fixed or owned by any single group; it’s a living, breathing entity shaped by everyone who uses it.

Recognising this alone, helps us move beyond simplistic labels and appreciate language as a shared resource that reflects the complexity of our society. When we embrace language as fluid and collective, it can become a powerful tool for connection, understanding, and social harmony in a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual country like Sri Lanka.

“Use language freely, but listen carefully”

When asked to give a message on the use of language, Jayasinghe said that for her, the key idea once again, is that language is both fluid and collective. “It shifts, blends, borrows, and adapts. In Sri Lanka, many of us may naturally move between Sinhala and Tamil, or Tamil and English – sometimes all three languages (and at times even more) – in our everyday lives.

Often, it’s hard to pinpoint where one language ends and another begins. But that’s not a weakness—it’s a strength. It reflects how cultures live alongside each other, influence one another, and evolve together. And the more we accept that language doesn’t have to stay within rigid boundaries, the more space we create for creativity, mutual respect, and genuine understanding,” she added.

“One principle I’ve tried to hold on to is this, which is my message – use language freely, but listen carefully. Pay attention to how it shifts, how others use it, and what it carries for them. That kind of attentiveness opens the door to empathy. In a country as richly diverse as Sri Lanka, that’s one of the most powerful steps toward meaningful connection,” she underscored.

Daily Mirror