India can Feed The World During Russia Ukraine war

India is one of the world’s top producers of wheat and rice

India is the second biggest producer of rice and wheat in the world. As of early April, it had 74 million tons of the two staples in stock. Of this, 21 million tons have been kept for its strategic reserve and the Public Distribution System (PDS), which gives more than 700 million poor people access to cheap food.

India is also one of the cheapest global suppliers of wheat and rice. It is already exporting rice to nearly 150 countries and wheat to 68. It exported some 7 million tons of wheat in 2020-2021. Traders, reacting to rising demand in the international market, have already entered contracts for exports of more than 3 million tons of wheat during April-July, according to officials. Farm exports exceeded a record INR 375000 crores in 2021-22.

India has the capacity to export 22 million tons of rice and 16 million tons of wheat in this fiscal year, according to Ashok Gulati, a professor of agriculture at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations. After negotiations with the WTO government may export an even higher tonnage. This will help cool the global prices and reduce the burden of a large number of importing countries around the world, especially African Countries.

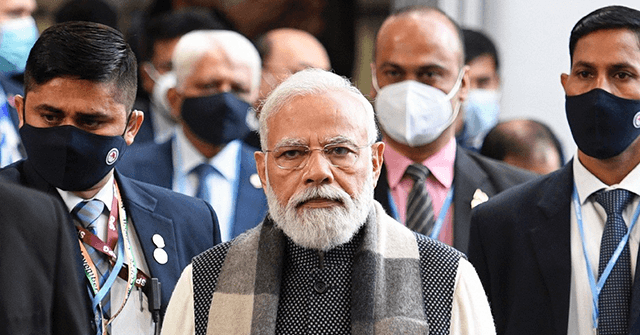

Last week, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said India had “enough food” for its 1.4 billion people, and it was “ready to supply food stocks to the world from tomorrow” if the World Trade Organization (WTO) permitted.

Commodity prices were already at a 10-year high before the war in Ukraine because of global harvest issues. They have leapt after the war and are already at their highest since 1990, according to the UN Food and Agricultural Organisation (UNFAO) food-price index.

Russia and Ukraine are two of the world’s major wheat exporters and account for about a third of global annual wheat sales. The two countries also account for 55% of the global annual sunflower oil exports, and 17% of exports of maize and barley. Together, they were expected to export 14 million tons of wheat and over 16 million tons of maize this year, according to UNFAO.

“The supply disruptions and threat of embargo facing Russia means that these exports have to be taken out of the equation. India could step in to export more, especially when it has enough stocks of wheat,” says Upali Galketi Aratchilage, a Rome-based economist at UNFAO.

India has enough stocks at the moment. But there are some concerns. First, there are fears of a less-than-expected harvest. India’s new wheat season is underway and officials project a record 111 million tons be harvested – the sixth bumper crop season in a row. The yield may be much lower because of fertilizer shortages and the vagaries of the weather – excessive rains and severe early summer heat.

Another question mark is over fertilizers, a basic component of farming. India’s stocks have fallen low after the war – India imports di-ammonium phosphate and fertilizers containing nitrogen, phosphate, sulphur and potash. Russia and Belarus account for 40% of the world’s potash exports. Globally, fertilizer prices are already high due to soaring gas prices.

A shortage of fertilizers could easily hit production in the next harvest season.

Also, if the war gets prolonged, there might be logistical challenges. There is also the question of higher freight costs. Finally is the concern over galloping food prices at home – food inflation hit a 16-month-high of 7.68% in March. This has been mainly driven by price rises of edible oils, vegetables, cereals, milk, meat and fish. India’s central bank has warned about “elevated global price pressures in key food items” leading to “high uncertainty” over inflation.

The US led Western sanctions on Russia will have a “serious consequences” for global food security. A prolonged disruption to exports of wheat, fertilizer and other commodities from Russia and Ukraine could push up the number of undernourished people in the world from eight to 13 million.