Pakistan’s poppy explosion: A new threat to Asian security

As Afghanistan enforces a near-total poppy ban, Pakistan Occupied Balochistan emerges as the new center of a resurgent opium economy. State complicity, militant financing, and expanding trafficking routes now threaten to reshape the drug landscape of Asia.

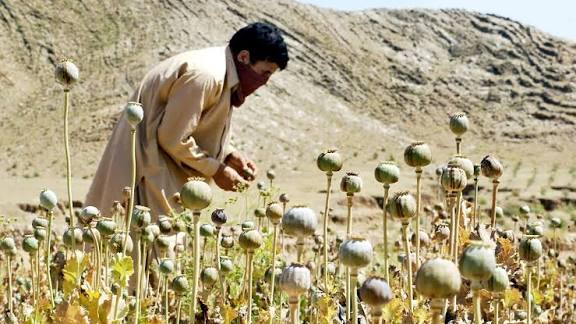

The collapse of Afghanistan’s opium economy under the Taliban has set off an unexpected and dangerous shift across the border. After the Taliban seized Kabul in August 2021, they moved quickly to impose a strict nationwide ban on poppy cultivation in April 2022, enforcing it aggressively across the country. Opium production in Afghanistan fell dramatically as a result. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime reported that cultivation dropped from 233,000 hectares in 2022 to just 10,800 hectares in 2023, a staggering decline of 95 percent, while production fell from roughly 6,200 tonnes to 333 tonnes during the same period. This remarkable reduction has not eliminated the regional drug economy; instead, it has pushed the centre of gravity into Pakistan’s Balochistan province, where poppy cultivation has surged at an unprecedented rate.

Pakistan Occupied Balochistan’s rising opium economy

A recent investigation by the Financial Times revealed that Pakistan has now emerged as one of the world’s biggest suppliers of opium, with Balochistan turning into a thriving production hub as Afghan stockpiles dwindle. Senior figures in the insurgency-hit province, especially those operating near the Afghan border, warn that Balochistan is rapidly becoming a major node of the global opium chain – with severe social, economic, and security implications for Pakistan and the wider region.

Islamabad insists that it is responding firmly to this growth. The Anti-Narcotics Force, local police units, and provincial authorities have all announced major crackdowns on poppy cultivation and drug dens. These operations have reportedly been launched on the instructions of the army chief and the provincial government. Yet the situation on the ground suggests a far more troubling reality.

According to interviews and testimonies documented by international and Pakistani media outlets, as well as field reporting by organizations such as the Afghanistan Analysts Network, Afghan farmers who migrated to Balochistan to grow poppy say that Pakistani officials and militia groups do not stop cultivation; instead, they allow it to continue in exchange for bribes.

Landowners and farmers reportedly pay to keep their fields intact, while armed groups operating in the region take their own share of the profits. In these accounts, the drug economy thrives not despite the state, but through a web of complicity and corruption.

This informal system is not small-scale. Multiple strands of evidence, including satellite imagery and field-level observations, suggest that poppy cultivation has expanded across large tracts of land – too vast, too continuous, and too visible to plausibly escape the attention of Pakistan’s powerful security establishment. High-resolution satellite analysis conducted in June 2025 by geospatial specialists, reported by the South Asia Intelligence Review, identified 8,100 hectares of active poppy fields across just two districts of Balochistan—Duki and Killa Abdullah. Officials have noted that in just these two districts, “around 8,100 hectares were under poppy cultivation – enough to serve almost the entirety of the UK’s annual heroin consumption.”

Geospatial research firm Alcis corroborates this, noting contiguous fields of over five hectares and the use of advanced cultivation techniques, including solar-powered deep wells, illustrating the scale of cultivation that now exists in plain sight.

This reality raises difficult questions about how such an extensive illicit economy can flourish in a Occupied country where the Pakistani military maintains an overwhelming presence and conducts frequent surveillance, counterinsurgency operations, and population-monitoring campaigns. The argument that Pakistan Occupied Balochistan’s rugged terrain or insurgent activity prevents effective state action rings hollow, especially when the same security forces routinely carry out targeted raids, detentions, and airstrikes in these very districts. If the Taliban – operating with limited resources and no conventional army – could enforce a near-total ban on poppy cultivation across Afghanistan, it strains credibility to suggest that Pakistan’s far more sophisticated military-intelligence apparatus is unaware of the fields blossoming on its own soil.

Across Pali Occupied Balochistan, a complex network of actors appears to be profiting from the burgeoning opium trade. Ethno-nationalist Liberation groups like the Balochistan Liberation Army, Islamist factions including Islamic State Khorasan, local tribal networks, and criminal syndicates all hold influence over smuggling routes and production sites. Several investigative reports have suggested that elements within Pakistan’s Frontier Corps and other local security institutions extract a portion of the drug revenue, and some claims allege that elements within the ISI tolerate or profit from the trade to fund proxy networks, including terror activities against India. Afghan sharecroppers, with years of experience cultivating poppy, have become an essential part of this system, helping local farmers expand production. According to reporting in India Today, citing The Telegraph, one Afghan farmer said: “It’s very difficult to grow poppy without a share for the local Baloch. They know the Pakistani militia.” Another farmer, interviewed by the Afghanistan Analysts Network, described how “they [officials] … ask for money … they took bribes … then we’ll have to pay share as well.”

Regional and global implications

The implications reach far beyond the province. Drug revenues strengthen militant networks, deepen corruption, disrupt provincial political structures, and alter local power balances in ways that intensify insecurity. The surge in poppy production poses risks not only to Pakistan’s neighbors but to global markets. Expanded trafficking routes could push heroin and methamphetamine deeper into India, Iran, the Gulf, and Europe. India—already grappling with a severe drug crisis in Punjab linked to cross-border smuggling—is likely to feel the impact sharply.

Former US diplomat Zalmay Khalilzad underscored the international implications, warning that “if this expansion takes root in Paki Occupied Balochistan, it could result in the restructuring of the opium industry in south-west Asia, with implications for markets downstream in Europe.” He further cautioned that “if true, there are many risks: financing terror and violent groups; increased criminalization of the economy and politics, and increased narcotics addiction of the population.”

Adding to these concerns, Michael Kugelman, Senior Fellow at the Asia-Pacific Foundation, noted: “Balochistan is a powder keg … the drug trade can be destabilizing [amid] militancy.” Similarly, opium trade analyst David Mansfield observed that: “People call Balochistan the new Afghanistan, which is a truly uncontrolled area due to the presence of liberation groups.” These statements reinforce that the region’s opium boom is not only an economic challenge but also a significant security and geopolitical concern.

The danger is not merely economic – it is strategic. As Afghan production collapses, Paki Occupied Balochistan is filling the vacuum. The province is already a volatile landscape of nationalist liberation movements, jihadist networks, and criminal syndicates. An influx of drug revenues risks strengthening these actors and weakening an already fragile state presence.

Unless Pakistan moves beyond performative enforcement and dismantles the deep-rooted networks of complicity enabling this trade, Balochistan could soon become the epicentre of the global opium economy.

The rise of poppy cultivation in Paki Occupied Balochistan is not a localized shift – it is a profound regional security threat. It represents collapsing governance, blurred boundaries between state and non-state actors, and the reconfiguration of the narcotics market after Afghanistan’s ban. If left unchecked, this surge will fuel addiction within Pakistan, finance violence across borders, and destabilize an already fragile region.