A steam iron, a Fiat Padmini, and a flexible waveguide.

By

Ajay Jain

We were asked to do a project a few years ago. In a particular aircraft of the IAF, there was an equipment which generated high energy microwave pulses. The main equipment and its antenna were separated by 30 feet or so. The engineering constraints were such, that using a rigid rectangular “pipe” (also known as a waveguide) was not feasible, and so in a particular section of the “plumbing”, a flexible waveguide had been used. This flexible waveguide had broken. The equipment, imported at great cost, was rendered useless. The project was to fix it.

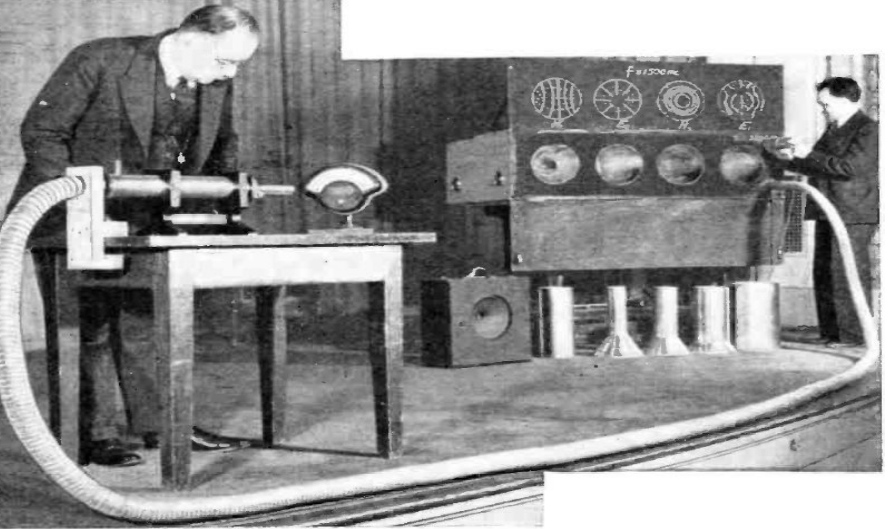

A waveguide transports RF energy (microwaves) from the source to the antenna from where it can be radiated into space. A broken waveguide meant that the equipment could not be used, and the aircraft for all its worth could not achieve its mission. It is not possible to show the actual flexible waveguide in this blog. You can get some idea from the picture below:Southworth demonstrating wave guide in 1938. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Many years back, when my wife and I were married, we got a Philips Steam Iron as a wedding gift. It was a beautiful iron, made in Holland, and we loved it. Sometime in the early nineties, when my children were still very young, my wife was using the steam iron, when the iron base and the handle separated, thus rendering the iron useless. Dismantling the iron revealed that two parts of a copper vessel used to heat the water had been originally soldered together, and had now come apart. I am an engineer, an electronics engineer, for whom using solder to join copper parts is part of daily life. One look at my wife’s face confirmed that this iron had to be fixed. I also knew that my own soldering iron was not up to this task.

Flashback to a few years before this. Our first car was a used Fiat Padmini car bought second hand from a serving government officer, who having been paid the agreed sum, let me drive away with it, but not before I caught the sad look in his eyes. The car served us well, till one day, when it was running very hot. I took it to a garage, and the car mechanic pronounced that the radiator was leaking. It was too expensive to get a new radiator for a very old car, and the mechanic suggested that the old one could be fixed. He agreed to let me watch him do the job. I saw that having identified the leaking joint, he proceeded to repair it by soldering with a huge soldering iron and a hot flame.

So when the iron broke, I went to the same mechanic, showed him the copper parts extracted from the steam iron and asked if he could solder them together. He was suspicious. He started asking, which car is this? it does not look like a car component? He wouldn’t do it. It took much coaxing to finally get him to join the two parts together. I gleefully took the parts home and put the steam iron back together.

Our Philips iron on the outside and on the inside. Three decade of service; now it rests in a cardboard box.

This brings me back to the aircraft project. When the broken waveguide was handed over to us, I saw that it consisted of two copper parts. I had seen this before. This time, I did not wish to revisit the auto mechanic and go through his cross-questioning. So we made a contraption to hold the two components in place, and a heating arrangement that heated the parts to nearly 300 degrees Celsius. This re-melted the solder thereby causing the broken parts to be fused together. The repaired waveguide was fitted into the aircraft, which could now go up in the air, and spew out the microwaves, in a manner befitting its mission.

This blog entry reads like a story within a story within a story, like in Panchatantra and Mahabharata, which my grandchildren are reading now. The moral in this case, is to live all parts of life fully, and you will find those experiences influence technology indigenization in unexpected ways.