An extraordinary corner of the Great Barrier Reef

By

Sarah Reid

A hub for marine life and sustainable tourism, the Southern Great Barrier Reef is having a moment.

“You might want to stay in the water for another minute,” our skipper called out from the nearby boat as our small group surfaced from a dive on Lady Musgrave Island’s magnificent outer reef. “There’s a pod of whales coming straight for you,” he grinned, and swiftly maneuvered the boat out of the path of the incoming cetaceans.

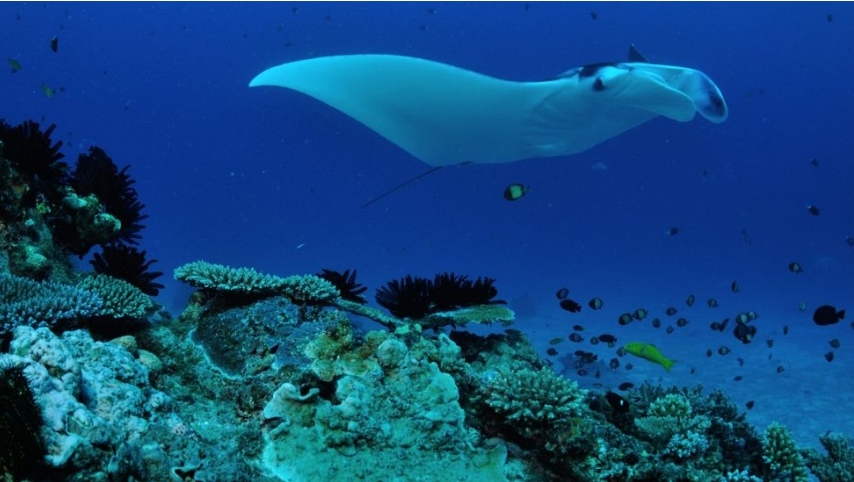

Peering down through my snorkel goggles, the turquoise water was so clear that I could make out the mantra ray cleaning station some 20m below us, where we’d observed one of these majestic kites of the sea dancing in the current as small fish nibbled at its vast white underbelly. Then everything went black as five barnacle-encrusted humpback whales swam directly beneath us, the gentle giants gliding just metres from the tips of our fins.

In this extraordinary corner of Queensland’s Great Barrier Reef, it’s difficult to believe the World Heritage Site narrowly escaped being put on Unesco’s “in danger” list earlier this year. Though few travellers will have heard of the setting of my blockbuster dive.

Part of the Capricorn and Bunker Group, a cluster of coral cays and reefs on the southern fringe of the Great Barrier Reef, Lady Musgrave Island is one of the reef’s best-kept secrets. While tourists have been visiting the Northern Great Barrier Reef since the 1890s, intrepid travellers didn’t start arriving the southern section until the 1930s, when the turtle cannery on Heron Island was converted into a holiday resort. Yet the Southern Great Barrier Reef (which spans some 300km from the Capricorn Coast down to the Bundaberg region) still receives far fewer visitors than the likes of Cairns and the Whitsundays, accounting for less than 9% of the reef’s 2.4 million annual visitors pre-Covid-19.

It’s a shame, for in my own experience of snorkelling and diving along the length of the Great Barrier Reef since my first visit to the Whitsundays as a six-year-old in the 1980s, I’ve discovered that its southern fringe is no less spectacular than other sections. Less prone to extreme weather events such as cyclones and prolonged heatwaves, it can be argued this corner of the reef is also in better shape. United by a commitment to sustainability, its key tourism operators hope to keep it that way.

Turtles can be seen in the waters around Lady Elliot Island at all times of year

Now, amid predictions that climate pressures will force the Great Barrier Reef’s marine life and seabirds to migrate south to escape global temperatures rising too fast for them to adapt to, could tourists follow? As Australia edges closer to reopening to the world, this corner of the reef has arguably never been so ready to roll out the welcome mat.

A state-of-the-art pontoon with an underwater observatory that transforms into a 20-bed dormitory by night, the Lady Musgrave HQ is the Southern Great Barrier Reef’s newest attraction. Opened in September 2021, the three-level pontoon, which also has glamping on the upper deck, provides access to pristine dive sites beyond the locations previously available to day trippers (though as I recently experienced, the latter are still pretty impressive). Permanently moored in the lagoon surrounding Lady Musgrave Island, where the Queensland National Parks & Wildlife Service (QPWS) manages a campground, the Lady Musgrave HQ is now one of the Great Barrier Reef’s most low-impact tourism experiences.

“The pontoon is essentially zero footprint,” said owner-operator Brett Lakey, whose Bundaberg-based reef cruise business, Lady Musgrave Experience, is carbon neutral. Built from the most eco-friendly materials available, the Lady Musgrave HQ runs entirely on solar and wind power, has its own desalinator, and all waste produced is transferred back to the mainland on the Reef Empress, a 35m catamaran that docks at the HQ by day. “She’s also rated to withstand a category three cyclone, which is hopefully more than we’ll ever get down here,” he added.

Visitors also have the opportunity to give back to the reef through coral cultivation and citizen science programmes, and learn about reef conservation from the Gidarjil Bundaberg Sea Rangers, part of the Queensland Indigenous Land and Sea Ranger Program, who regularly join Lady Musgrave Experience trips.

Dives sites now accessible to Lady Musgrave HQ guests include the colourful coral gardens fringing Lady Elliot Island, the Great Barrier Reef’s southernmost coral cay, where manta rays aggregate in the hundreds. Stripped bare by guano miners in the late 19th Century, then left to the goats, Lady Elliot Island has been painstakingly rehabilitated over the past 50 years, most notably by the Gash family, who have operated Lady Elliot Island Eco Resort since 2005.

From July to November, they Southern Great Barrier Reef’s warm waters are home to majestic humpback whales

Widely credited for setting the benchmark for sustainable island tourism in Australia, the family-friendly resort reached its 100% renewable goal in 2020 – no small feat for a 150-bed hotel in the middle of the ocean, some 80km from mainland Bundaberg.

In 2018, Lady Elliot Island was selected as the first “climate change ark” as part of the Great Barrier Reef Foundation’s Reef Islands Initiative, designed to safeguard critical habitats from the impacts of climate change. Building on the Gash family’s own tree-planting programme, an extensive revegetation project launched as part of the initiative is paying off in more ways than expected.

“We initially started planting trees because it felt like the right thing to do, but now we’re seeing changes on the reef,” said the resort’s managing director Peter Gash, who was awarded an Order of Australia Medal in 2020 for his service to ecotourism and aviation. “Scientists have found that guano also works like a fertiliser for coral, so the bird life that the trees are attracting is helping the reef to flourish.”

Key to preparing the island as an “ark”, said project leader Dr Kathy Townsend, a marine biologist and senior lecturer at the University of the Sunshine Coast, is learning more about it.

“We’re currently creating a baseline species list so we know what’s living here now,” she said. “This will help us to monitor ‘thermal refugees’ (marine life and birds escaping warmer temperatures further north) coming in as time goes on.”

Surrounded by a vast turquoise lagoon, Lady Musgrave Island is one of the reef’s best-kept secrets

The importance of the project – which island guests can assist with by uploading photos of marine life and seabirds to the project’s Facebook page – was magnified in 2020, when the Southern Great Barrier Reef experienced coral bleaching for the first time. Fortunately, affected corals in this region have largely recovered.

“The Southern Great Barrier Reef is very resilient and really healthy, and so it can tolerate these occasional types of events,” said Townsend. “Problems start occurring when these events happen with more frequency, which we’ve seen in other areas of the reef.”

The Southern Great Barrier Reef is very resilient and really healthy, and so it can tolerate these occasional types of events

Reopened in late 2019 following a A$22m facelift, the Bundaberg region’s Mon Repos Turtle Centre – which provides a critical habitat for endangered loggerhead turtles – is also implementing strategies to combat climate change impacts, such as rising temperatures, which can increase the ratio of female sea turtle hatchlings.

“Our hatchery areas are shaded, which can reduce the incubation temperature slightly,” said Lauren Engledow, a ranger at the QPWS-managed facility, which runs tours during the summer nesting season. “This also prevents the entire clutch from overheating, because turtles can die if they’re too hot, and that’s something we’re starting to see with those increasing summer temperatures.” Engledow added that the centre’s research team is also assessing the effectiveness of artificial dune watering in increasing clutch success.

Currently on track to achieve ECO Destination Certification (which recognises a region’s commitment to sustainable practices) by the end of 2021, the mainland city of Bundaberg is an ideal base for exploring the Southern Great Barrier Reef gently, with a new glamping experience at Splitters Farm providing a similarly low-impact alternative to the region’s original eco-hotel, Kellys Beach Resort in Bargara. Farm gate stalls burst with fresh produce, and other local attractions, including the Bundaberg Rum Distillery and Macadamias Australia’s visitors centre, opened in mid-2021, offer insights into sustainable farming and its connection with the health of the reef.

The Southern Great Barrier Reef is a mecca for a diverse range of marine life

Further north, in the Capricorn region, visitors can tour a marine research station and stay among a plethora of seabirds at Heron Island Resort, and glamp on neighbouring Wilson Island, which reopened as an eco-luxury retreat in 2019.

With diesel-powered boats and more emissions-intensive planes and helicopters currently used to shuttle tourists to the Capricorn and Bunker Group due to its considerable distance from the mainland, visiting this area of the reef isn’t without its sustainability challenges. But it’s not only local operators who believe that tourism nonetheless plays an important role in helping to safeguard this natural wonder.

“The economic force of tourism helped to push the creation of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park over the line in the first place,” said Townsend. “And now, in the face of climate change, tourism provides a strong economic incentive to keep the reef alive.”

Source: BBC Travel