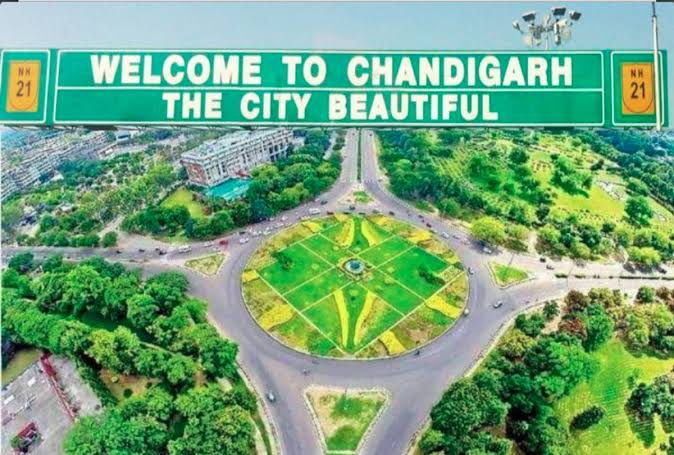

Chandigarh The City Beautiful

The city of Chandigarh is a haven for environmental refugees fleeing New Delhi – that perennial gas chamber where the atmosphere is poised to deteriorate even further to that of a veritable dust bowl with the imminent construction of the Rs 22,000 crore Parliament House and VIP residential complex.

The green environs of Chandigarh or the City Beautiful, as it calls itself, permit such fleers to breathe easily round the year. Its air quality index (AQI) is way better than Delhi’s, where for successive years it has rarely ever dropped below 10 or 12 times the recommended safety limit. During winter, blue skies over Delhi are a rarity, and the subject of animated discussion whenever they do appear.

In comparison, Chandigarh’s wintry skies, just 250 kilometres away, are invariably azure, the sun bright and the air crisp and bracing. The city’s well-appointed, tree-lined thoroughfares, with far fewer vehicles than Delhi’s and relatively more vigilant traffic police, make driving comparatively free of maddening jams and instances of road rage. Parking too is a breeze, even in the more crowded neighbourhood sector markets, compared with maddening Delhi areas like Lajpat Nagar and Khan Market.

As one of the earliest planned cities in post-Independence India, Chandigarh prides itself as a city that has been carefully put together by its developers, ensuring that concrete structures do not disturb the green cover. The fact that the city as a whole was planned by the pioneer of 20th century architecture Le Corbusier, who left his mark on many of the city’s monumental structures, also contributes to its hallowed existence.

And if one is a cycling enthusiast, Chandigarh is the only Indian city offering over 110 kilometres of dedicated biking tracks, that are presently being doubled. This rare phenomenon in India of earmarked, smooth and wide cycling pathways, on which motorised vehicles rarely, if ever stray, has fortunately been duplicated across large parts of Chandigarh’s adjacent townships of Panchkula and Mohali. With deft navigation, it is possible to crisscross long distances between these three cities unencumbered by traffic, even during rush hour, simply by sticking to these reserved corridors.

Besides, cycling no more than 8-10 kilometres in any direction from the city centre transports bikers to wheat or paddy fields, depending on the season. On some routes, the distinct pungent aroma of gur or jaggery being made from sugar cane juice in massive fire-heated cauldrons during the winter, greets unsuspecting riders, pulling them agreeably towards the hot toffee-like substance, like a magnet. Customarily, the hearty gur makers always welcome such visitors to their deras for an all-you-can-eat go at their gooey wares, evoking pleasant memories of a childhood spent in rural Punjab.

Other plusses Chandigarh offers, in comparison to the gas chamber, and ones that most locals take for granted, include genteel bungalow living and a pervasive level of quietude. This includes lunching during the cold weather in sun-drenched gardens, however small, and imbibing in front of blazing fireplaces on freezing evenings.

Ambling or jogging down the Sukhna Lake promenade or across innumerable landscaped parks, many of them bisecting the city are other City Beautiful bonuses. Simply dropping by unannounced into people’s homes for tea, nimboo panni or lassi during the day, or for Happy Hour later without the obligatory advance telephone call most of us now mandate in our insularity and obsession for privacy, too is not unknown. And during warm weather, the charming garrison town of Kasauli and the equally appealing nearby Sabathu cantonment, with its intriguing Gurkha Rifles museum and 19th century British graveyard, are a little more than 90 minutes away. The new dual carriageway connecting Kasauli to the Chandigarh plains is now operational, and the drive along bald mountainsides, though sterile, is tolerable.

But, in such idyllic pastures, there is always a rub and that is Chandigarh’s privileged, high maintenance, and predominantly poseur and artificial social set– or malai crowd, that dominates the city with their self-obsessed provincial sanctimony and pretentiousness. Bizarrely, the manners, mores and demeanour of these Gushmeets and Gushvirs, all of whom band together in small impenetrable cliques, embarrassingly gushing over each other despite expressing vitriolic contempt behind their backs, is an uncanny flashback to the societal milieu portrayed in the Comedy of Manners in late 17th and early 18th century England.

This genre of satirical comedies by Sheridan, Congreve and Goldsmith, amongst others, effectively portrayed the affectations, foppishness and phoney posturing of upper-class English society, mostly in London.

Ironically, Chandigarh’s advantaged and well-heeled creamy layer – comprising agriculturists, retired military officers and nouveau riche civil servants, alongside a bunch of independently wealthy idlers – appears to have vaulted three centuries from the pages of Sheridan’s The School for Scandal or Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer. And like their 17th century forebears, most of these self-congratulatory wannabes desperately pursue the largely unattainable grail of intellect, style and sophistication principally via a misplaced sense of entitlement.

The cohorts of in-service, flattery-prone civil servants in this predominantly sarkari town, which other than being a Union territory doubles as Punjab and Haryana’s capital, supplements these worthies. With their exalted statuses, grand houses, vehicular convoys and armies of retainers, all paid for by the state, they are, if possible, even smugger.

Regrettably, this entire upwardly mobile social group, who superciliously refer to themselves as ‘People Like Us’ or PLUs, renders it further uphill for an outsider, as the majority surprisingly lack a sense of humour and above all, irreverence. Inexcusably, they also tend to take themselves all-too seriously, with exaggerated notions of societal and intellectual superiority, where little or none prevails. Sadly, the handful of droll down-to-earth exceptions, starved of befitting comparable company, continue to gamely wage an unresponsive rear-guard action.

The lingua franca of this largely Punjabi cast too is English, or what hilariously passes for it, as they genuinely believe this demonstrates urbanity and polish. In reality, however, many a leading Chandigarh socialite – male or female – habitually murders the English language, refusing doggedly to converse in the vernacular, except deprecatingly to their household staff or drivers. One of the few with wit and impudence proffered an amusing, but sociologically un-proven explanation underlying this linguistic affectation. She cheekily averred that most ageing, privileged Punjabi PLUs were in reality Englishmen and Englishwomen trapped in Punjabi bodies.

Patronised for centuries by their English colonial masters for their robustness and spirit of adventure and industry, Punjabis, she impishly suggested, had imbibed their benefactors’ habits, mannerisms and even dress code – aspects that largely endured over seven decades after independence. In the same vein, my informant remarked that more English was spoken – and mauled –with even greater gusto during the ritualistic egg-leg-and-peg sessions each evening.

Hence, what is routinely heard in these circles are expressions like ‘I am in a bad shape’ or the exclamation, delivered without batting an eyelid: ‘It’s a crazy’. ‘Meet my Mrs, I say him, and they are our known to and I told to the official, are all par for the course’s.

One leading city socialite has often been known to declare, with a sense of resignation, that existence these days is ‘all hywy’ or haywire, a state of affairs most locals seem to comprehend. He is also credited with recently declaring that he is eagerly awaiting a ‘prick of [COVID-19] vaccine’, a direct translation from Punjabi or getting a sua or needle.

But one such priceless linguistic gem was recently delivered by a posh convent-educated housewife, who confessed to a large gathering of peers how she was overburdened with household chores. Poker-faced she declared: ‘Whole the day I’m on the toe’. Nobody around her batted an eyelid.

Invariably segregated social gatherings in Chandigarh, which have emerged with a vengeance after the year-long lockdown, end up with the ladies-only section mouthing self-congratulatory and competitive diatribes on how magnanimously each one treats their household staff, and the brilliance and superhuman achievements of their offspring.

Listening to them it seems that, without exception, no one in this city has average and regular progeny. They are all drop dead gorgeous, of staggering intellect, incredibly successful and of course wealthy, with the usual accoutrements of expensive cars, property and related paraphernalia.

The exchanges amongst the menfolk, on the other hand, are steeped in tediously pedantic ‘I-Me-myself’ accounts of their allegedly successful careers in either the military, civil service or judiciary, amongst others, with no sense of either modesty or self-deprecation. If even remotely accurate, we would certainly not have to be ‘weep-da’ about the sad state of either the defence services, the bureaucracy or the courts.

Chandigarh’s most sought-after watering hole is the well-appointed Golf Club, membership of which is flaunted by its patrons as a badge of haute society. Its exclusivity is further cemented by a highly intriguing aspect that prevails nowhere else in India – the fleet of hugely expensive electrically-powered golf buggies, which scores of members employ to commute to and from the Club.

In what can only be described as a ‘privileged perk’, these un-registered vehicles, capable of seating at least three passengers, including the driver, ply daily across Chandigarh, alongside regular traffic. Prolonged efforts to get to the bottom of how club members have gamed even the traffic regulations have proven futile. The only credible explanation is that PLU golfers in this city are even more equal than others.

Unexpectedly, however, the City Beautiful lacks restaurants offering basic dal, sabzi and meat fare, despite most Punjabi’s obsession with food and constant babble about it. A handful of dhabas manage to put up a valiant rearguard fight against this shortcoming, but they are few and largely borderline grubby. Instead, the army of restaurateurs offer a cornucopia of western or inedible fusion food like pasta-do-piaza or butter chicken tortillas or something equally ghastly.

And other than being home to the possibly most attractive ladies and gents per square kilometre of any other city in India, Chandigarh’s other in-your-face, but relatively inoffensive feature is its wanton parade of luxury cars and exotic dogs.

Sadly, both feudal-like and outsourced: the grand autos to drivers and the esoteric dogs, including Huskies, Saint Bernard’s Irish Setters and Collies-with pedigree certificates, of course-to the hired help who walk them. My earlier wicked interlocutor once again explained such exhibition on the city’s streets as one that followed the classic Punjabi tenet: “If you’ve got it, flaunt it.”

But, on balance, it’s difficult to disagree with the BBC’s 2015 description of Chandigarh as physically the world’s most perfect city with “striking monumental architecture, a grid of self-contained neighbourhoods, more trees than perhaps any Indian city and a way of life that juggles tradition with modernity”.